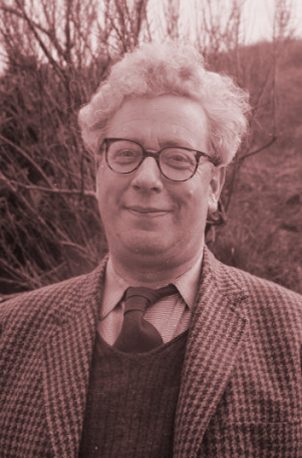

Daniel Jones is one of the most important Welsh, or indeed British, post-war composers. He left a large body of works in virtually all spheres of creative activity – thirteen symphonies; eight string quartets; a large body of chamber music; incidental music; opera (The Knife and Orestes); several cantatas; and concertos, the three most notable of these being for Cello, Oboe, and Violin.

Born in Swansea, he was at first encouraged to study English literature in Swansea University where he graduated with first class honours, later taking his MA for the study of Elizabethan Lyric. His boyhood friend, Dylan Thomas, became the internationally known poet and their relationship is colourfully captured in Jones’s memoir My Friend Dylan Thomas (1977). Jones composed the award-winning music for Under Milk Wood and would later edit Thomas’s poems including several examples of the poet’s early work. Their word games as boyhood friends no doubt inspired both their work.

Following on from his studies in Swansea, Jones studied conducting in the Royal Academy of Music – these were the first years of professional performances of his early chamber music in particular. During the war, Jones famously worked in Bletchley Park as a Captain in the Russian-Japanese section (he was a gifted multi linguist). This interest in complexity stemmed from childhood and resulted in his formulating a concept of what he called’ complex metres’. After the war, he eventually returned to Swansea where the bulk of his mature work was composed.

His First Symphony was a watershed in Welsh music when it was performed at the Swansea Festival. There followed another twelve symphonies, together with eight String Quartets, which are surely one of the most distinguished series in post-war British music (think of the series by Elizabeth Machonchy for example). His output is of the British symphonic sonata-allegro principle, coupled with rhythmic ingenuity and experimentation, and a harmonic language based on rather than in tonality.

Daniel Jones’s system of complex metres is underlined in the Sonata for Unaccompanied Kettledrums which was formulated during the 1940s particularly during his time in Bletchley Park, but also from his period studying and travelling in Europe as the winner of the prestigious Mendelssohn Scholarship. During these years, other composers were experimenting with metre and they included Boris Blacher and Elliott Carter. Jones’s notion of following (for example) 9/8+3/4+2/4+6/8+2/4+2/8+3/8 lends to the music a characteristic ambiguity. The Sonata utilises rhythm as a structural element within a sonata-allegro framework and milieu. As one of the composer’s earliest published works, it rapidly gained international acknowledgment.

String Quartet (1957) again employs the sonata-allegro principle in idiomatically written string discourse. Thematic material is highly organised, and thematic links are ever-present throughout. The four movements are called: ‘Agitato’, ‘Lento espressivo’, ‘Allegro risoluto’, and a final ‘Agitato’. In themselves the titles reflect the content – Jones was to use ‘espressivo’ and ‘risoluto’ extensively (particularly in his chamber works) and they perfectly capture the spirit of the music.

The Country Beyond the Stars is a cantata for chorus and orchestra composed during the late 1950s with the capabilities of choral resources of the South Wales valleys in mind. Indeed, the renowned Pontarddulais Choral Society gave the first performance with an enhanced BBC Welsh Orchestra. Further performances were given by (for example) the Swansea Philharmonic Society under Haydn James. It sets the visionary poetry of Henry Vaughan and does so within a tonal base, with lyricism and dramatic intent in turn. From the opening chorus through to the final triumphant ending, the piece is surely one of the most attractive works of its kind in post-war British music.

(The score followed by two pages of the pencil sketch.)

Dylan Thomas’s play for voices, Under Milk Wood, is internationally renowned as one of the poet’s finest works, written as it was in the years immediately before the poet’s untimely death on 9 November 1953. The characters heard include some of the most colourful in literature and they underline the very ‘Welsh’ nature of this unique piece – amongst them Evans the Death, Rosie Probert, Rev. Eli Jenkins and Dai Bread. Jones would later edit the play for the first performance but also wrote the prize-winning music for that performance and it remains unique in being naturally folk-like and simple without ever sinking into simplicity. The songs were recorded in Laugharne School thus complementing the authentic atmosphere.

Chamber music was central to Jones’s work. Surprisingly for such a fine pianist, he wrote little for the instrument after discarding a considerable body of works composed in his youth. His first set of Bagatelles was composed during 1943-5 and explores a wide range of emotions and pianist textures. In this manusctript, II-V correspond to 1-4 in the published edition. I and VI were not published although VI was recorded by Llŷr Williams on the disc of Bagetelles by Tŷ Cerdd.

The second set, presented here in full, was composed between 1948 and 1953. It displays a growing compositional confidence and freer use of dissonance and complex metres than the earlier pieces.

The third set, originally titled Seven Pieces for piano, was composed in 1955 when Jones’s work was receiving wide recognition outside his native Wales. From the opening bars of its first piece, a Bartokian Allegro, through the eerie quality of the second, in which gently flowing lento misterioso triplets accompany an ambiguous melodic line, to the rhythmic complexities of the fourth, the technical brilliance of the fifth, the reflectiveness of the sixth, and the highly-charged seventh, these Bagatelles mirror the composer’s own multifaceted character. They deserve to be hallmarked as great chamber music.